If you are reading this now, and you have the opportunity to take pause, simply listen. Wherever you are - it’s clear that what you are hearing is not the lack of sound, or presence. Silence is loud. There is always something living in it. It is the way we begin to really hear what is happening in the world around us, in the movements of those near us, and in ourselves. A week in silence is more about fullness than absence.

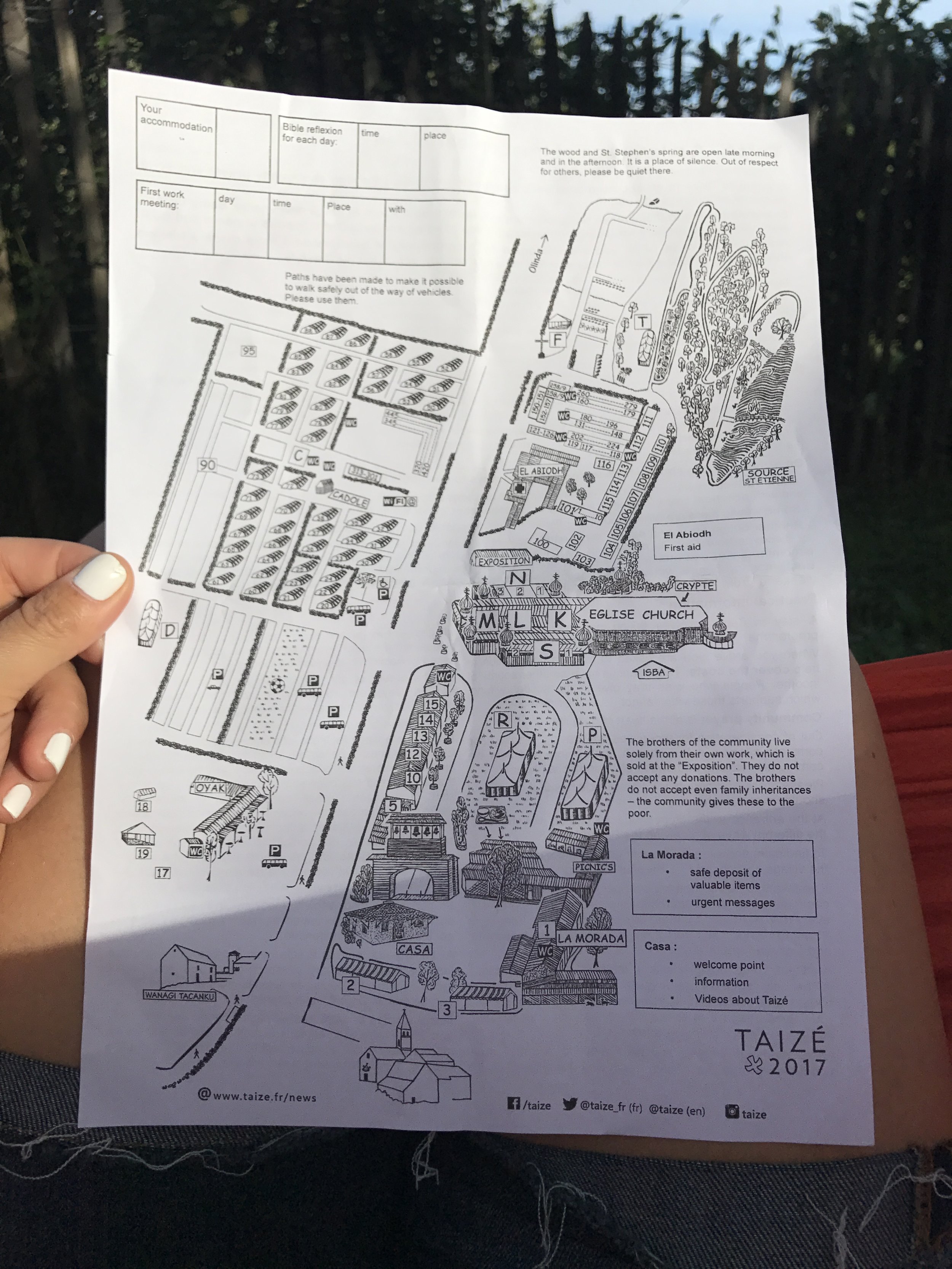

A few weeks ago I had the opportunity to spend a week in silence in Taizé. Taizé is a community in Southern France run by an order of monks who choose to devote their lives to creating a space for young people to encounter silence, song, and the sacred. On any given day in the summer, the small town is overrun by five thousand young people and a small assortment of people older than “young”.

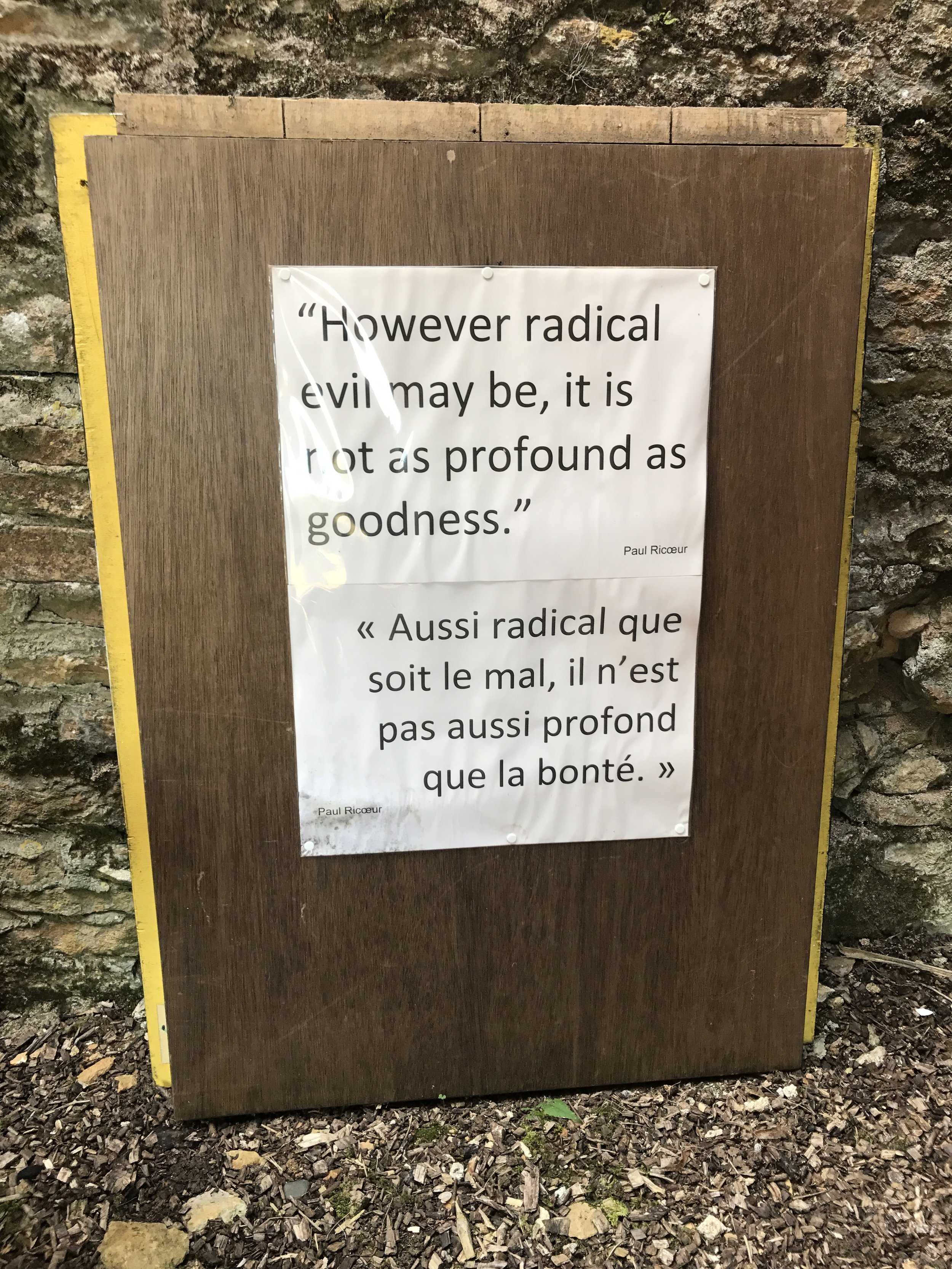

Taizé was originally created by Brother Roger in the aftermath of World War II. Prejudice abounded in France towards Germans, and Brother Roger chose to set up in a part of France specifically designed to encounter “the enemy”. This spirit of reaching out to the stranger and the outcast has continued to this day. The week prior to my arrival Taizé had bravely hosted a series of workshops on encountering refugees in Europe.

A week of silence for most meditation instructors is a bit of a rite of passage. Up until this, I had done retreats with evenings of “companionable silence” (i.e. nod hello, say please and thank you, but don’t speak until after breakfast). I have also done days of silence through Jefferson’s Mindfulness Program. I wanted my first experience with prolonged silence to be in the contemplative Christian setting. I hope to do another week soon in a more ecumenical setting.

For those not familiar, although most conventional American church services today will bear no more than thirty seconds of silence before feeling pretty squirmy, the Christian tradition as a whole has a contemplative meditation practice going as far back as the first century - only roughly forty years after the writing of the latest composed Gospel. Taizé provided me with a chance to see what one interpretation of meditative silence could look like.

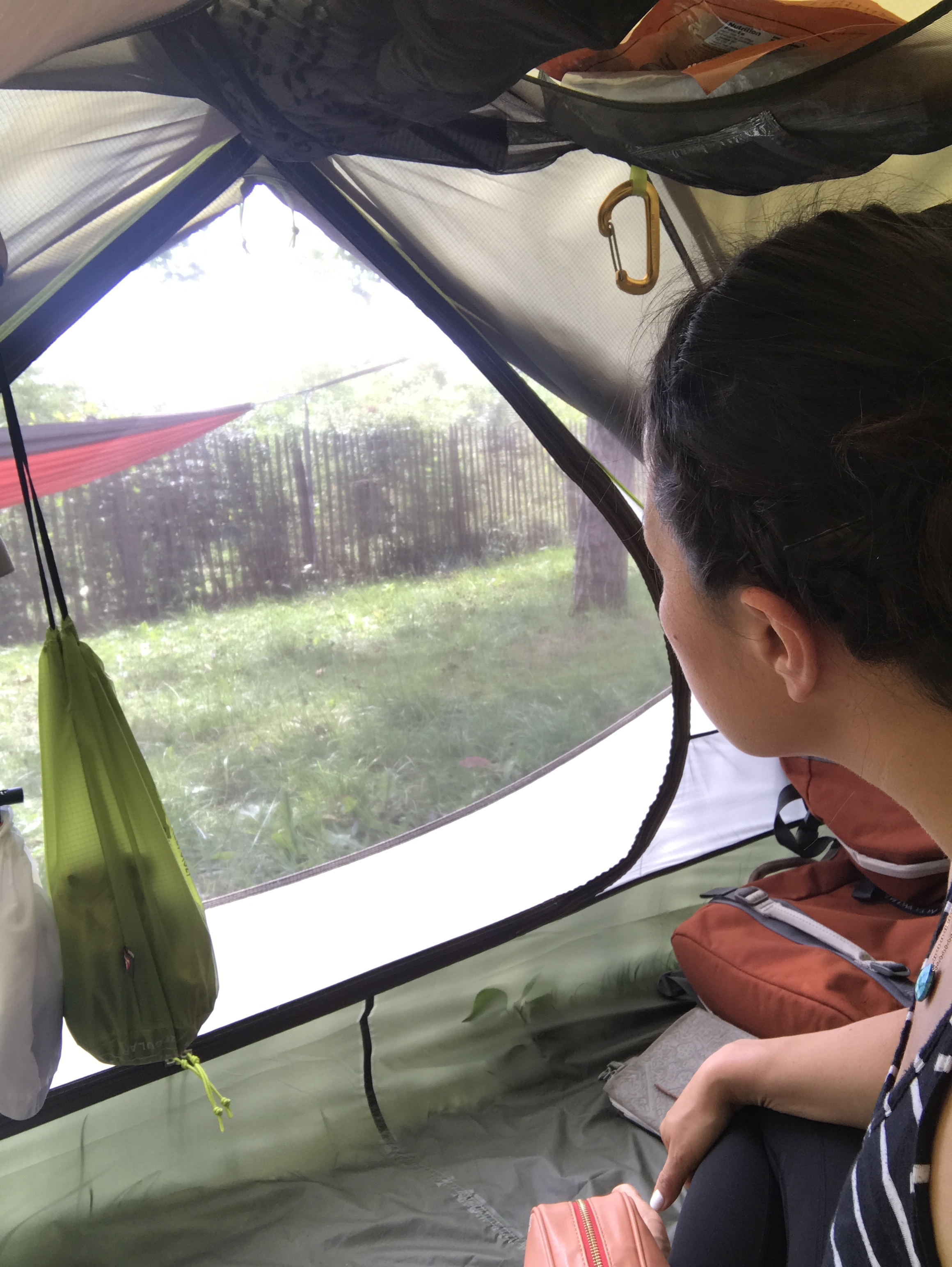

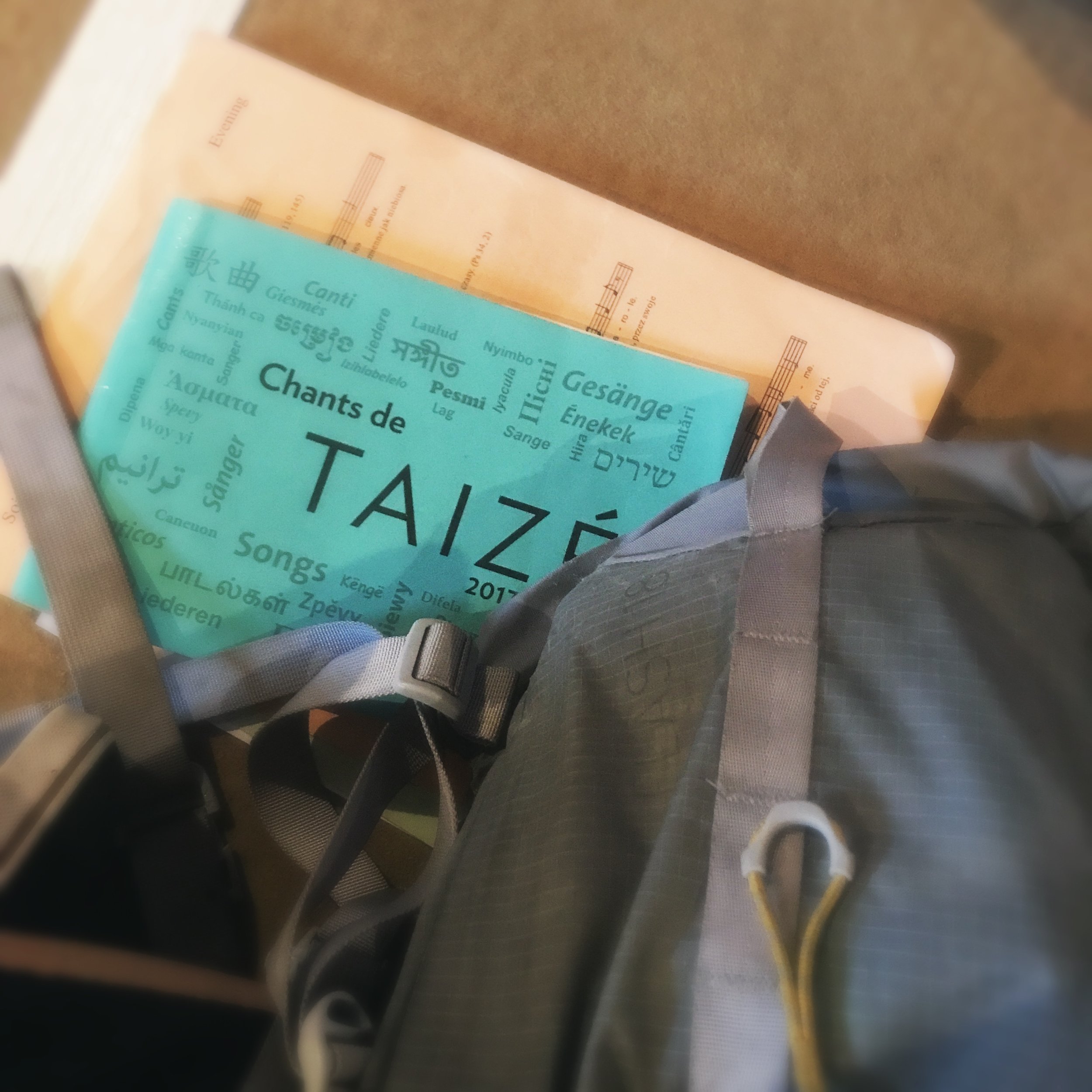

Every morning I wake in a tent on a French countryside. Most mornings it has just rained. About fifty visitors are sequestered in a corner of Taizé’s property specifically designated for silence. Morning prayer takes place seated in a large, modern auditorium at 0815. There is singing in more than four languages, yawning, and communion. The first food you have every day is the sacrament - that is - if you want to receive it. After morning prayer, I wordlessly meander through a crowd of young people to find my fellow silent sojourners under a tent. We eat a piece of bread, butter, jam, and powdered hot drinks looking out over the countryside.

Once the dishes have been stacked and sent away, we stare out at the field in front of us until Sister Croix arrives. The sister rides in on a bicycle. Her hair is cropped. She has glasses. She usually wears an orange sweater which she inevitably removes about twenty minutes into meeting. She smiles as she speaks. And she speaks at least three languages: German, English, French. Sister Croix arranges for translators and within no time, her words are - sentence, by sentence - being transformed into Korean, Polish, German, and French. She explains that silence is more about learning to listen than it is about learning to cease talking. She says we will be silent unless we need to speak, or unless we would like to sing. She gives us a few passages to study, some suggestions about a style of reading scripture called lectio divina but she doesn’t call it this - she simply tells us to read, to listen, to write down what we think, pray the ‘Our Father’ “and then Basta”.

We mosey away from this meeting a bit stupefied. When she says, go be quiet and pray, we think, ‘But how?’ When she explains these passages of the Bible that we have heard a thousand times, they sound different: new. She says of the paralytic brought to Jesus, ‘We are all paralyzed sometimes. But healing does not happen because we ask for forgiveness, it happens before forgiveness occurs, and then we - in response - wake up, and carry our stories home with us’.

In front of my tent, I have set up a hammock. I sit in the hammock occasionally waving away the bees, reading, writing, listening - still stupefied. I am surprised what comes from nothing.

Midday prayer is at 1220. The bells ring again and the whole of humanity in this small place is drawn in our hungry stupor to the chapel again. Midday prayer is songs, kneeling, the reading of the Bible in six different languages. Then lunch happens. Lunch is bigger; mostly vegetarian. There is always a way to squirrel away a bit of extra cheese or fruit. There’s also time to indulge in that most revered of silences: the post-lunch afternoon nap. This is good because it’s a long time until dinner. This is also glorious because silence is sometimes sleep.

In the afternoon we are encouraged to be active in some way; to wander out into a field, stretch our legs, or in my case, find some movement to be doing. Every day I’m there is an adventure in navigating the humans in Taizé finding my penchant for intensity a bit out of place and trying not to set my workout on top of an anthill. There are horses, sheep, cows, and geese wherever I go. It’s grand, beautiful - about twenty degrees celsius - and sunny.

After being active, I sit down in my tent with both vents open, eat my squirrel snack, and start reading and listening again. My breathing is elevated and this makes meditation easier in some ways. I am less tempted by the surrender of sleep. Instead, I walk out into the sun, and feel the warmth of the day, the din of the green world around me, and distant voices.

Then, at 1800, it’s time to wash the bathrooms. With a chorus of Italian, Brazilian, and British women I am staring at my reflection in the mirror, scraping hair from the sinks - for a blissful moment - discussing the correct translation for ‘squeegee’. I figure out how to refill soap and paper dispensers with humble glee. The work is wonderful. We feel for a moment, I think, that we have an occupation, a service, some great thing such as this - a clean bathroom - to offer our fellow pilgrims. We serve each other without a word. We smile softly and communicate relief and satisfaction when we are done. We take down our makeshift “closed for cleaning” sign with redemptive fervor.

I walk through the dust to dinner. I sit on the grass and think over, and over, about how the trees really do look like they are clapping their hands. I clap my hands for dinner at 1900 too. Dinner is about as big as lunch - with an occasional surreal piece of fish or sausage. Occasionally, we run out of food. Occasionally, I notice someone chewing. One night, there is only yogurt for dinner and since we are silent - we just sit and eat in spite of ourselves. I think often on these nights that it’s incredible how much of our lives are spent complaining or wishing for things that just won’t come.

If I have skimpy dinner, though, I lean heavily on the jerky that I have trekked from the U.S. to Switzerland to France. I eat this in the gloaming before evening prayer - my favorite service of the day. At 2030 there is a sense in the chapel that we are dying to the day, that we do not know that we will resurrect to our mornings filled with bees and bread. It is all up to chance. There are candles flickering, and my soul feels peaceful. The light of day leaves the windows and we walk out of the chapel into the great quiet of the night.

I sit in my tent, nursing a pocketed piece of chocolate reading a novel, or checking on the world outside of this canvas. In the distance, I hear a throng of young voices singing. They are more than a choir; they are insistent. A bit closer, I hear a violin playing out Taizé songs; simple melodies that sound like you know where they are going or where they have been even if you are hearing them for the first time. I can hear my neighbors rolling over in their beds, rustling in the leaves, the thoughts in my head.

This is what a day is like. And there’s more than this to say, but I think the silence is meant to be a bit of a secret. You must go there to find what it says to you, what you are always saying to yourself.

What I have learned about a week in silence is that the first few days are a relief. By the third day, everyone wants to laugh: about the flimsy benches that we all keep forgetting to measure when we sit down and fall over, about the way the men have decided to clean the bathrooms shirtless because it is insufferably hot, about how we are filled with so much but saying so little. By the fourth and fifth day, we are a bit more somber, with revolving doors for brains, praying without ceasing.

On Saturday - the last day many of us are there - we are bowled over with love. We are the poor in spirit, and we have seen God. We cannot contain ourselves, though we do not know each other’s names. I hug the women I clean with. I smile at the vegan who gave me all her protein all week long. A man I have never spoken with gives me a card and a candle and blesses me with a saying from Teresa of Avila. Sister Croix says, ‘Maybe tonight, and all nights we can just think of three things we are thankful for, say thank you, the Our Father, and then Basta?’

One man cries out for the rest of us at our last meeting, “What should we do at home? What will we read?” Another says, “Why does everything you are saying to us sound so different than what is sounds like at home?” Sister Croix grins, and says, “Who said it was supposed to be easy?”

I sit in the glow of the day waiting for the bus thinking about what I could say about silence (ah, the irony...). The truth is even now, I feel that my words can’t speak for silence. The silence is ineffable - shouting at us that all of the burdens, business, and bullshit that we throw in the way of “what is” chokes what surrounds us. We can love in action more than we think. We can hurt with words more than we would dream. We can hear more in the quiet than we have spoken into it.