This past summer I was fortunate enough to be gifted a course in Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (or MBSR) through Jefferson's Myrna Brind Center. During our first year of marriage, Arrus and I got the chance to dedicate 3 hours of every Wednesday evening to attending this 8-week course. Though 3 hours in the middle of the week is a big commitment for any busy individual and certainly was for us, I am so glad we invested the time - this course was nothing short of life-changing.

What is mindfulness? It is the everyday practice of moment-to-moment non-judgmental awareness.

I have always been someone who approached fitness from the perspective of what it has been able to do for me spiritually, as well as physically. I know not everyone sees it that way, and that's fine enough. For my part, I love that movement allows most of us to feel alive (even if at the end of "Fran" we are pretty sure we are actually dead). I love that there is a curiosity inherent to beginning CrossFit that is almost as magical as the way that children first learn to walk, crawl, run, look in a mirror, and find out what falling feels like. I love that the changes we can experience through good nutrition and lifestyle habits can alter our perspective on our relationships, our days and - let's face it - our lives. CrossFit Center City exists because I have a serious addiction to bearing witness to these changes.

Sometimes though, a lot like mixing paint colors, all these colorful changes in so many lives can blend into black or worse, like a muddy gray. Life can become muted and dull in spite of being around so much vivid color. This is what mindfulness has given me: a lens to look through when the picture is too big to absorb properly. And, true to form, I want to share this with all of you. Here is what the last year and a half of learning about mindfulness taught me about being an athlete.

1. Everything I do is impatient.

Even as I write this post I want the words to come more quickly. I have found that impatience is one of my central characteristics as a person and as an athlete. I have the sneaking suspicion that many of you are in this boat with me. To be impatient is not all bad, you get a lot done most of the time when you don't like waiting. As an athlete this may be reflected in the way you take on new challenges, learn new skills, and wait with baited breath for the whiteboard to appear.

But when you rush (and when I rush!), you miss everything. In fact, you literally miss the thing that you most wanted. Maybe you miss the intricacy of a movement pattern unfolding before you. Maybe you miss the moment that your WOD rabbit revolutionized your world. Maybe you miss celebrating the success of another or hearing someone celebrate yours. Maybe you're simply skipping a step.

It's old news, but good news: it's a relief to stop, take a look around and really get a chance to release yourself from the constant pressure of what you are eager to become, and instead breathe in the air of what you are.

2. Mindfulness is falling awake, even if you're falling asleep…

Confession: with early starts and late nights and well, being human - I struggled to stay awake through about 90% of my time in MBSR (Mindfulness Based Stressed Reduction Courses). I would spend my first few sessions wishing I had prepared better, slept more, been able to be a higher order of being and able to stay awake for unlimited amounts of time. I soon found that there were tricks to waking up: drinking coffee even though it wasn't the most zen beverage of choice, opening my eyes instead of closing them, and sitting in postures that were best for me and not always pretty.

But I eventually realized, I may always be tired. I may never be perfectly prepared. And that may never change.

Like, literally NEVER for the rest of my life.

In your training, you may always have to favor the mornings or the evening WOD after a long day. You may be in on a Saturday after another night out spending your recovery on Buffalo Billiards (been there, guys - skeeball!). You may have kids/family/spouses/roommates/dogs who keep you from doing ___fill in the blank____! Whatever your situation is, you may be powerless to change it, but you can change your attitude towards that very moment. You have the power to make the very moment you are reading this more alive than the moment before it.

You have the power to open your eyes.

3. The distraction is the meditation.

In our very first mindfulness class there was a bumblebee.

An actual bumblebee.

This softball-sized (slight exaggeration) bee was hovering above us all. And who were we? A small cohort of doctors, working professionals, new mothers, grandmothers, nurses, teachers, therapists, ex-convicts, and cancer patients - all earnestly attempting to shut out the sound of a bumblebee in an otherwise empty room. We debated openly: Could anyone remember if bumblebees were vindictive enough to sting you? Would this one bend that way? Would you be next for the swoop or me? People literally screamed... in Mindfulness Class... On the FIRST day.

I'm still not sure if that bumblebee wasn't planted as a test for us by the Myrna Brind Center. But here is what I have learned through Maddox interrupting my 2k time trials, a drop-in kindly asking for my attention 15 minutes into my training session, or simply the fact that something will ALWAYS be happening when I am rolling out my yoga mat to stop for 5 minutes - when you have noticed that you are distracted, this is the meditation.

That is the very moment that you are now here, and not "there" anymore. Embrace it. Learn from it. Try not to judge yourself for wanting it to be different. Welcome it as what was meant for you and be curious as to why.

4. Pain is perception.

In the last year or so my Coach has gone from giving me the daunting task of doing six 500m Row repeats on a Saturday by myself in a corner (after strength work, after 4 hours of coaching), to giving me twelve (TWELVE!) 500m Row repeats on a Saturday by myself in a corner (after strength work, after 4 hours of coaching). The funny part about all of this is that I thought six was bad...

What in the name of all that is good has this taught me?

That pain is a great teacher. Resent, even more so.

Those of you who know me, know I am not a great rower and I'm not an athlete who comes to CrossFit with a broad conditioning bias (unless you count my being biased AGAINST conditioning) - despite having ACTUALLY rowed in a boat at one point in my life.

I think rowing in particular is a daunting task for most of us not because the act itself is incredibly difficult but because our pace, our limitations, and our perception of the length of the task is ALWAYS very clearly in front of us. Aside from an Assault Bike piece (which many of us haven't even had the pleasure of really delving into) rowing is the only thing you'll do in CrossFit that will show you where you are the ENTIRE time.

If you are not keen to accept the present, you will spend the majority of your time on erg fearing what's next, or thinking of how you have felt before. Raise your hand if you have spent an entire 2k dreading the last 100m. The more time you spend doing this, the less time you spend focusing on the task at hand: this pull, this recovery, that breath. You are missing the entire point: to be rowing.

I row faster than I ever have today (even if that's not saying much relatively) and the majority of my improvement has come from one thing: I am not afraid anymore.

In mindful meditation, you will sometimes be asked to sit with what is uncomfortable. Literally, sometimes in the most ill-adapted position, or with an itch that you want so badly to itch. You will sometimes be asked to simply observe your pain (emotional or physical), examine it, identify the flavor, the scope, the texture - and to watch how your body responds.

Oddly, sometimes when you do this, you will find that the pain was never there at all. This, friends, can have a powerful effect on your performance, as well as your perspective.

5. May you be as strong as YOU can be.

One of my favorite meditations from my time in my first Mindfulness course was called the Loving Kindness meditation. While it sounds relatively fruity (and really, it's ok if it doesn't resonate with you - not everything will!) there is one part of it that felt just right for CrossFit. There is a variation of it here. Within the course of this meditation, you will go from a series of sort of wishes that you will attempt to give to someone who is easy for you feel kindness to, to giving them to yourself, to giving them to everyone around you. The script of the wishes goes as follows:

May you be peaceful and happy.

May you be safe from harm.

May you be as healthy and strong as you can be.

May you live with ease of well-being.

It's a shock to the system to go straight from the striving of every day at CrossFit Center City to hearing this and attempting to a) accept it, but b) give it. I have been doing CrossFit - that is - keeping score, encouraging people to aim for more, straight-up weeping alongside athletes who feel they are not good enough, and ultimately, striving for growth in every direction for the last nine years of my life.

What if you could stop all that and simply accept that right now, you could aim to be as healthy and strong as YOU can be - not as someone expects you to be, as you expect you to be, but simply, as you can be - right in this very moment? What if you could give that kind of grace to someone else?

I think the journey becomes more joyful. I think the goals seem more like a part of your story instead of a threat. I think the people around you seem more like companions than competition.

It's a brave hope, but that is the best thing about now - it is actually the only moment in which change is ACTUALLY possible.

How can you start learning more about Mindfulness?

As a start, I'd say that the HeadSpace App is incredibly helpful, especially if you're short on time and/or money, and definitely a very easily approached way to begin practicing. This will provide you with 10-minute pieces for lots of different situations, but it will also take you through a short beginner's program to give you the lay of the land in your mind.

I would also highly recommend attending a drop-in session through Jefferson's Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction program. They host sessions that are only $20 to drop-in from time to time. You can find more information about that here.

Related specifically to Mindfulness and the life of an athlete I would highly recommend CrossFit Invictus's book, The Invictus Mindset: An Athlete's Guide to Mental Toughness. Invictus also has a series of Meditations and Visualization Practices that you can use for cool-downs before bed, or after a workout. Visualization is not Meditation, but it is closely tied to the practice.

If you're a bit spooked by this whole thing and just generally need to feel more mobile and maybe a little more chill, you can also check out a trial membership at ROMWOD - ROMWOD is not for everyone, but there are daily posted videos that run between 20-40 minutes of very gentle stretching specific to the needs of CrossFitters. There's also some guided breathing and occasional touches of mindfulness and visualization that are different every day and also searchable by specific body part needs.

Finally, CFCC's Stability WOD class aims to provide about 10-15 minutes of Mindfulness Meditation at the end of every class. I am not a certified instructor by any stretch of the imagination, so I often use recordings I have found, or scripts that I have been able to experience myself. I think this variety has been helpful, but for any of my steady attenders out there - let me know if not! We spend about 45 minutes to reset movement patterns, and the remainder of class trying to take a hot second to allow for some time to listen to our bodies. You know how people are always saying that with regard to injury: "Listen to your body,"? Turns out, you actually have to make time to do that so that your body doesn't have to start screaming...

If you have any questions about Mindfulness or any of the above, please feel free to reach out. This has been a topic that I have continued to spend more time with in the last year since my summer course in 2015 and I'm very passionate about allowing others to experience the relief I have been privy to through my time in meditation. I also really had to work hard to only write about five things in this blogpost. As I've said, it's not for everyone, but for those of you who feel that any part to this resonates with you, I'd love to help you in any way I can.

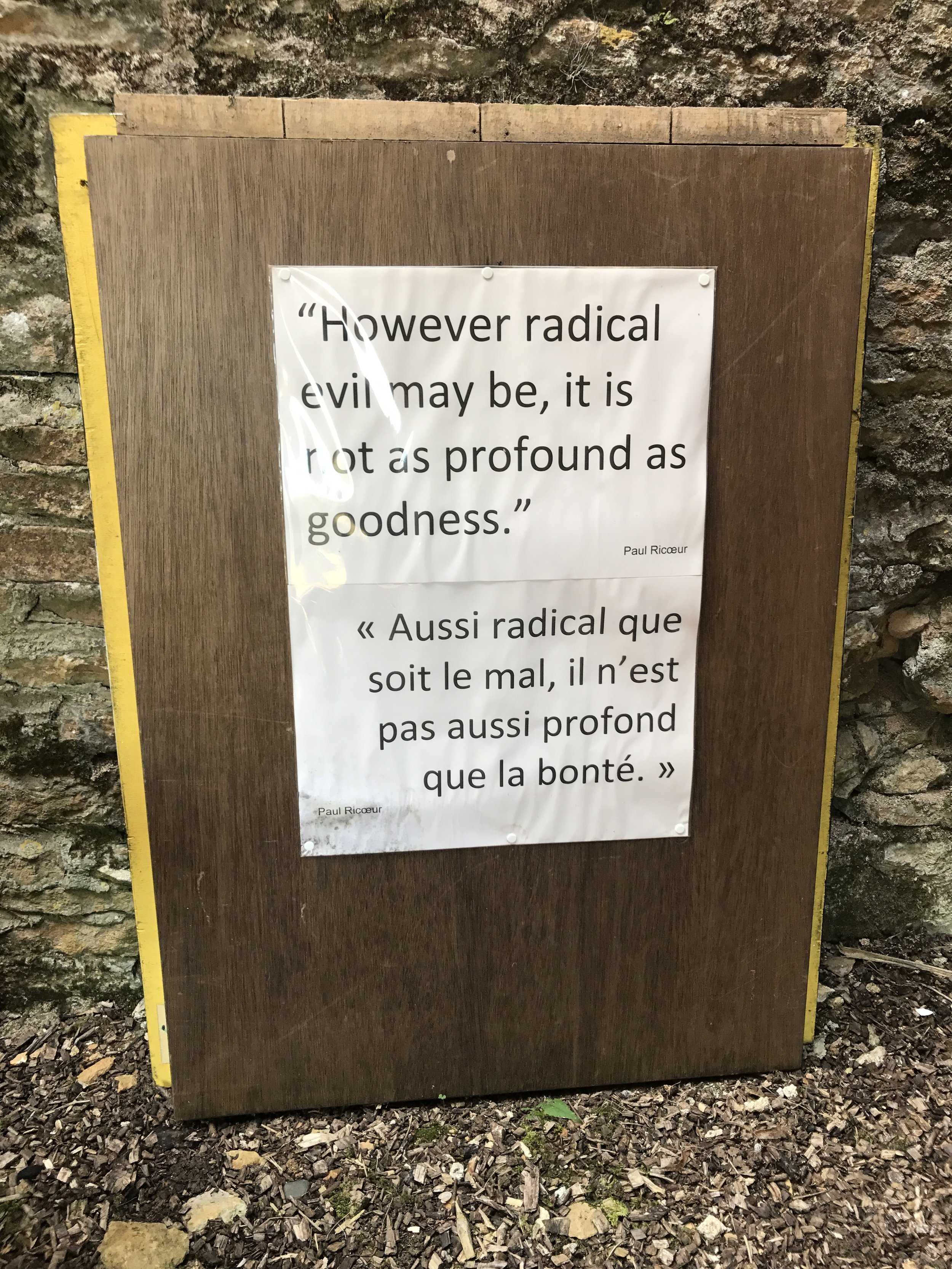

I'll leave you with one of my favorite quotes:

"You cannot move forward from some idealized point in the future that has not yet arrived. If you are to move forward, you must do it from where you are now. Though it may not be perfect, it is plenty to get you going. Wishing for more, or feeling resentment because you don't have more, will only waste your precious time. Although there is no guarantee that your actions will be effective, one thing that is certain is that nothing will happen if you take no action at all."

- James FitzGerald, aka OPT